Your World Class Education Partner in Smart Classroom Solutions

Schoolnet provides transformative education solutions through tech-enabled classrooms, AI-led learning, teaching and school management solutions.

25+ Years Of Impact At Scale With

100,000

Schools

25 million

Teachers & Students

30

States & UTs in India

7

Countries Globally

Bringing Edtech Innovation to K-12 Schools and Students

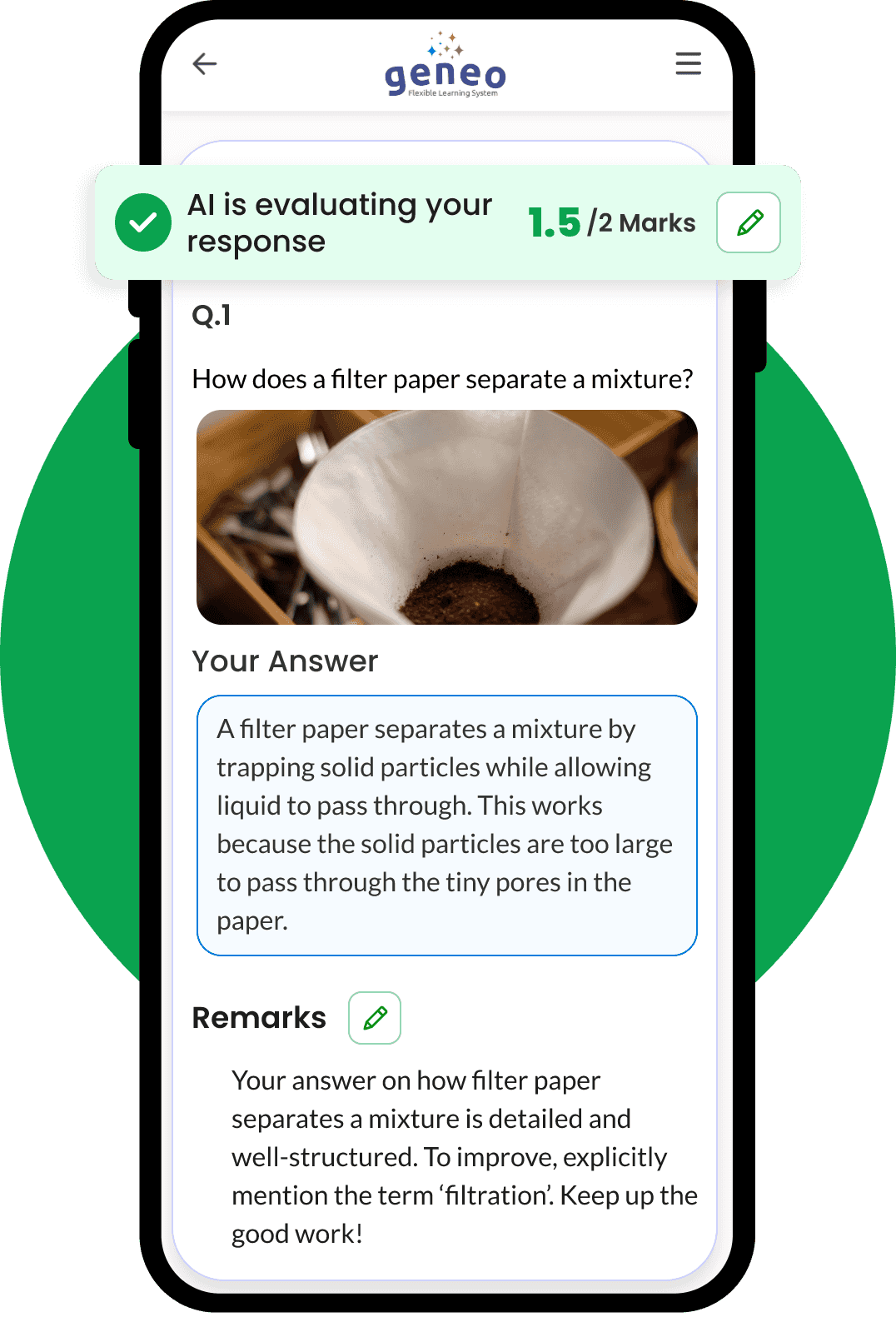

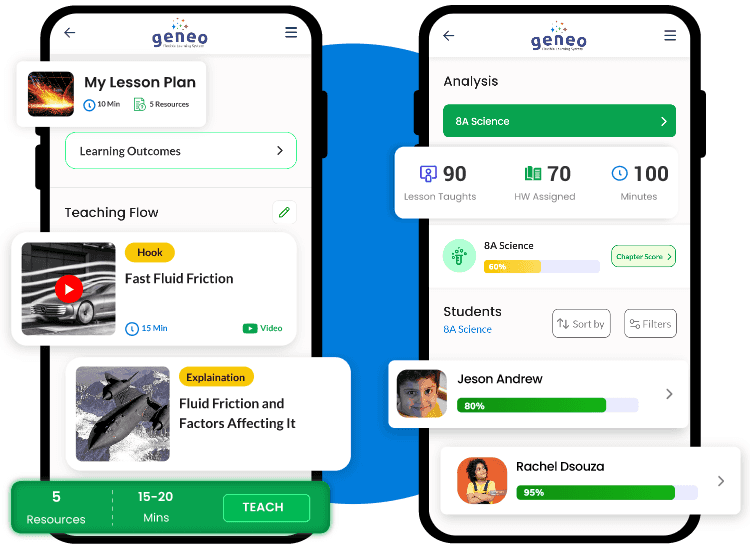

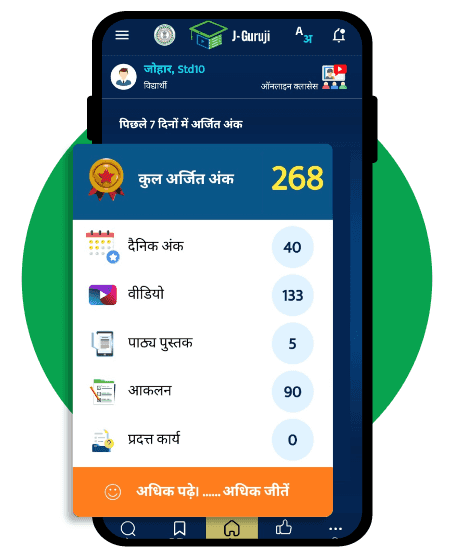

Geneo AI Apps

School & after-school sync solutions with AI-enabled apps for teachers and students.

Learn More

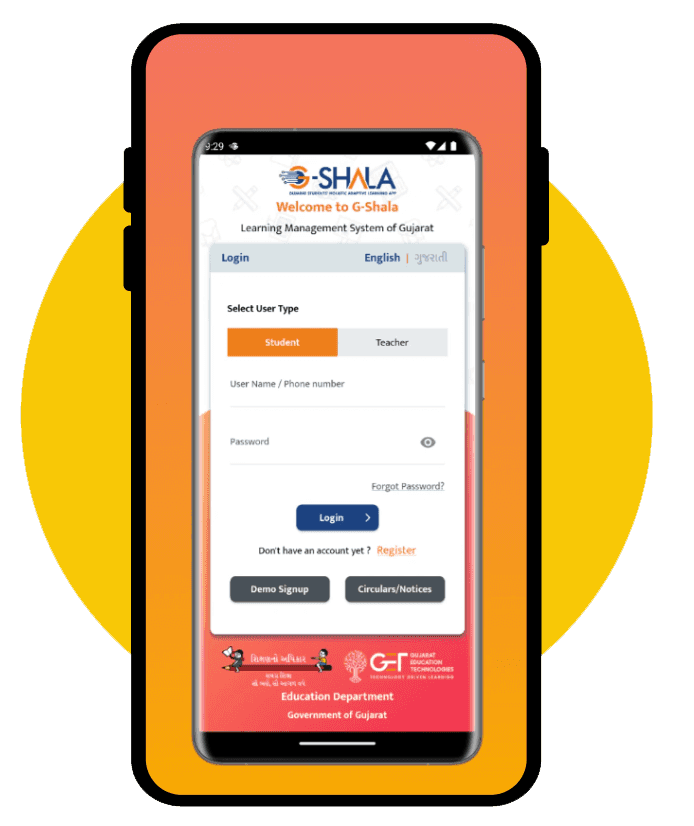

Centralized LMS

Transforming state-wide education through centralized solutions by managing schools across districts.

Learn More

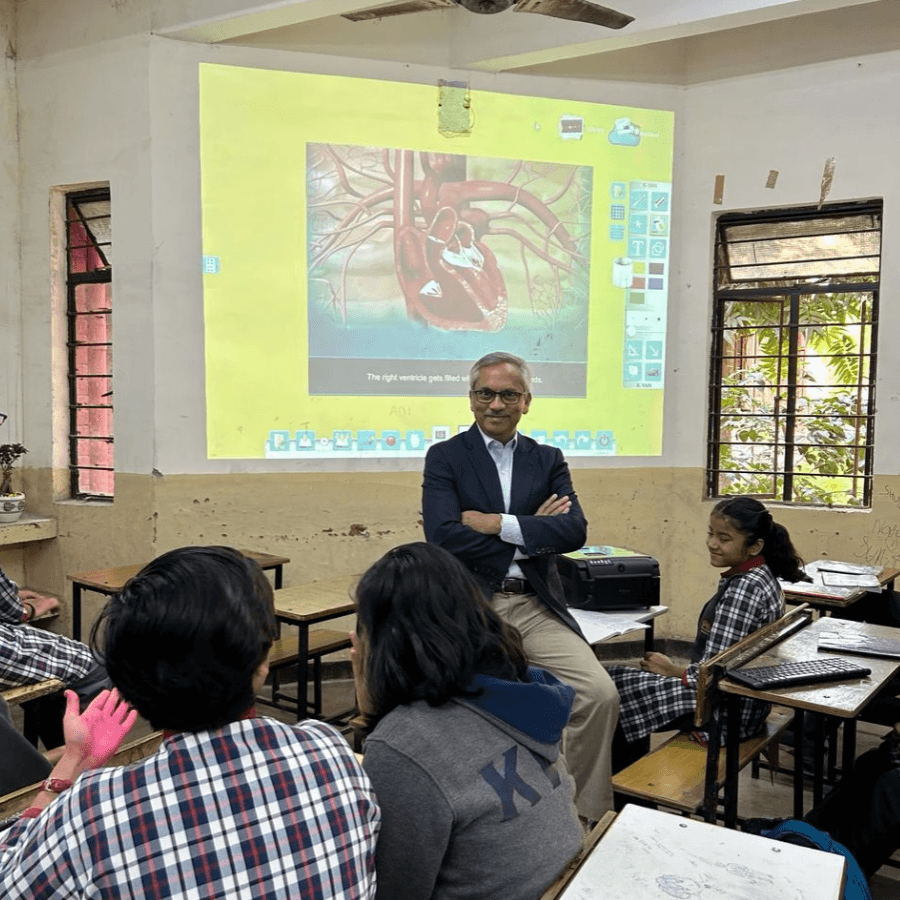

Smart Classrooms

Digital solutions for classrooms with interactive offline content to make learning faster, smarter, and larger.

Learn More

Our Trusted Partners

Ready to Bridge the Digital Divide in Your Classrooms?

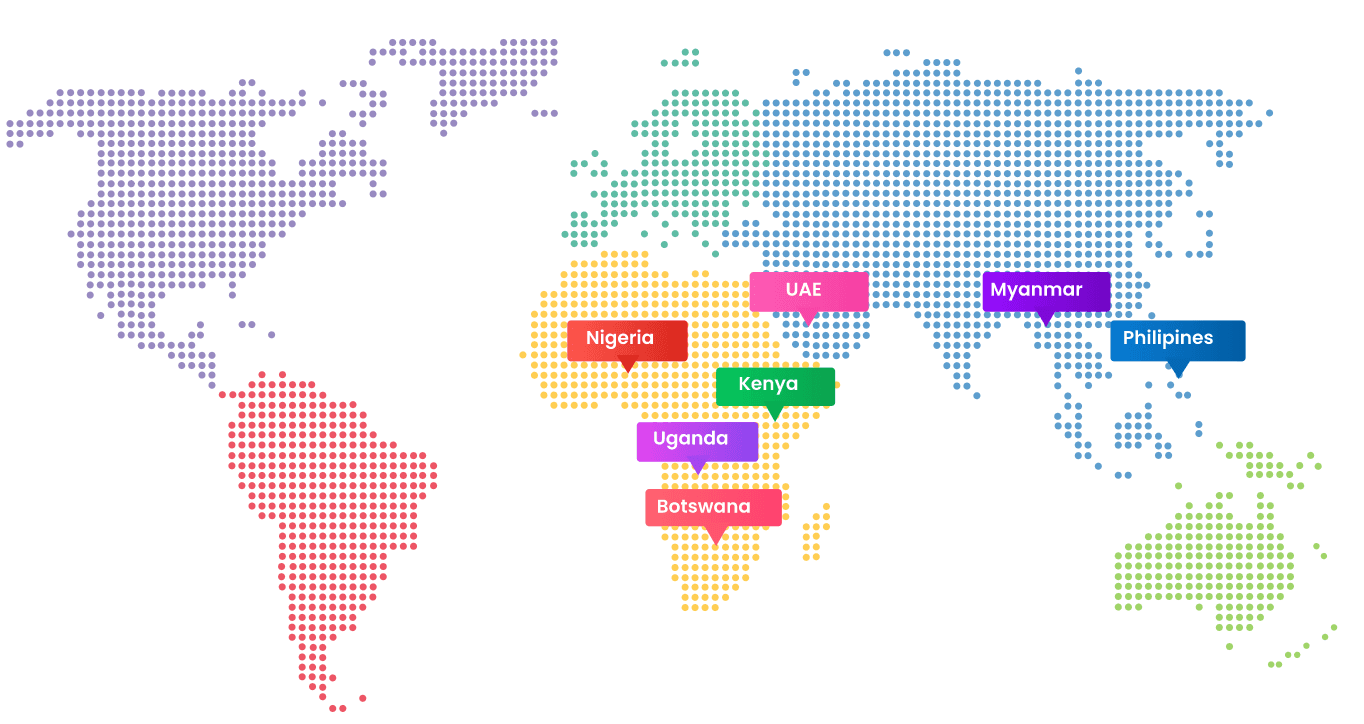

Our Global Footprint

Bringing High-Quality Indian Education Ecosystem to the World

2000+ Classrooms

Content that Connects

We have created customizable educational content that is based on National Curriculum Framework (NCF), local curriculums & real-world problems for more than 8 major State Boards with CBSE across India

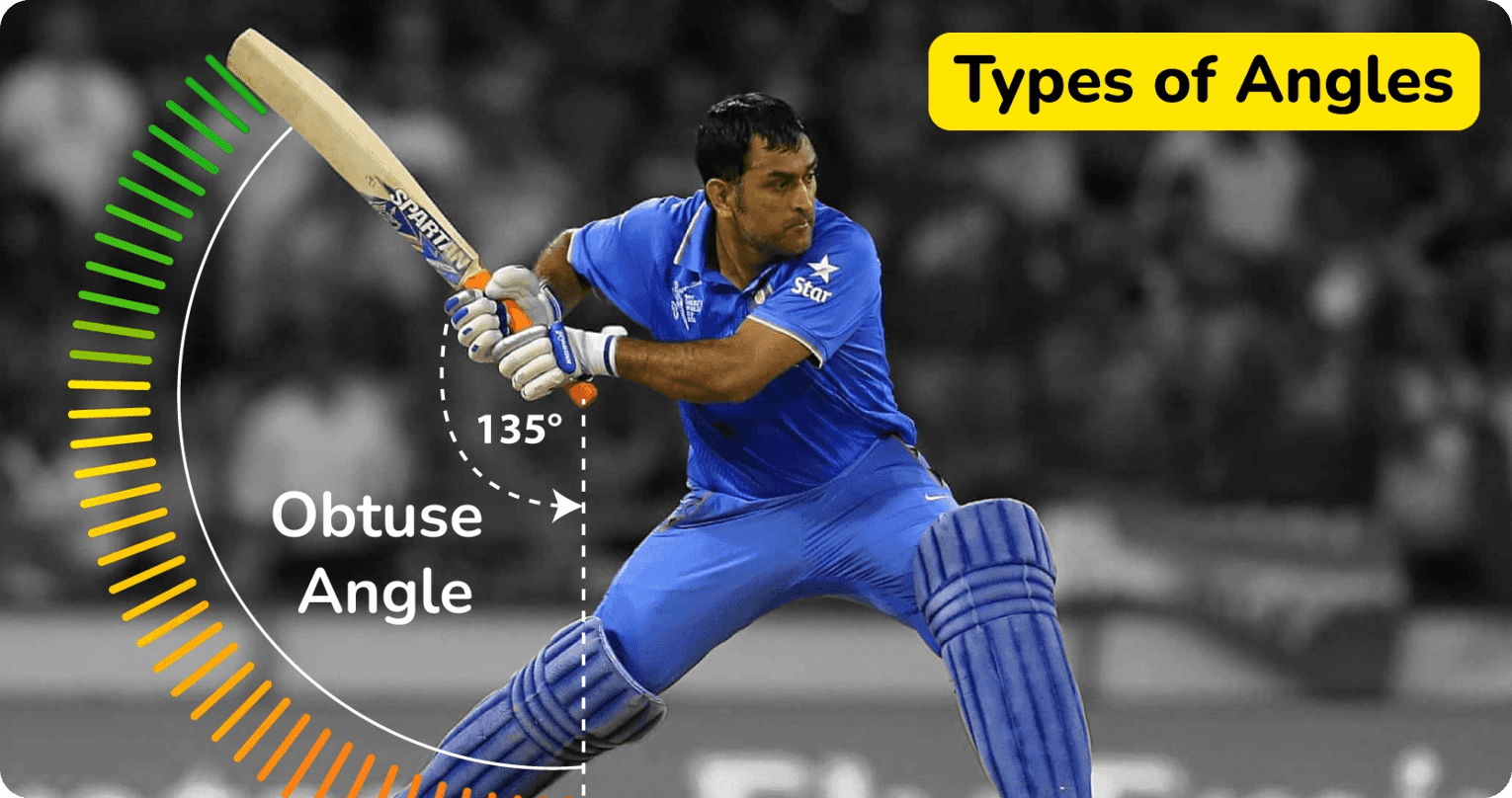

Real-World Examples

Digitized Assessments

Interactive Class Exploriments

9

Boards

8

Languages

NEP

Aligned

Want to Make Learning Fun & Engaging Again?

Schoolnet in News

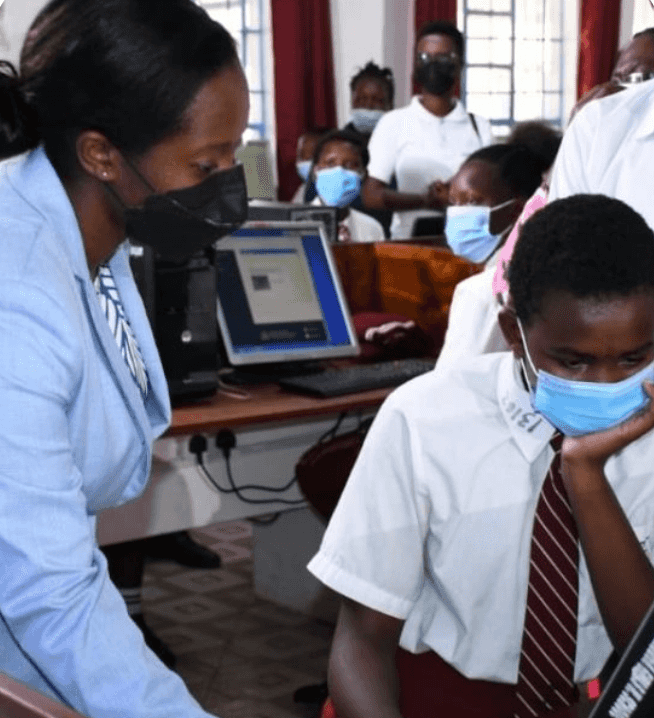

Every Teacher, a Genius Teacher.

Empower today's educators for tomorrow's learners. NEP-aligned Curriculums supported by Digital Learning. Bridging Traditional & Modern Pedagogy.

1 Million

Teachers

2 Million

Training Hours

NEP

Aligned

See What Our Trusted Partners Have to Say

Our Latest in Social Media

Awards & Recognition

© Schoolnet India Limited